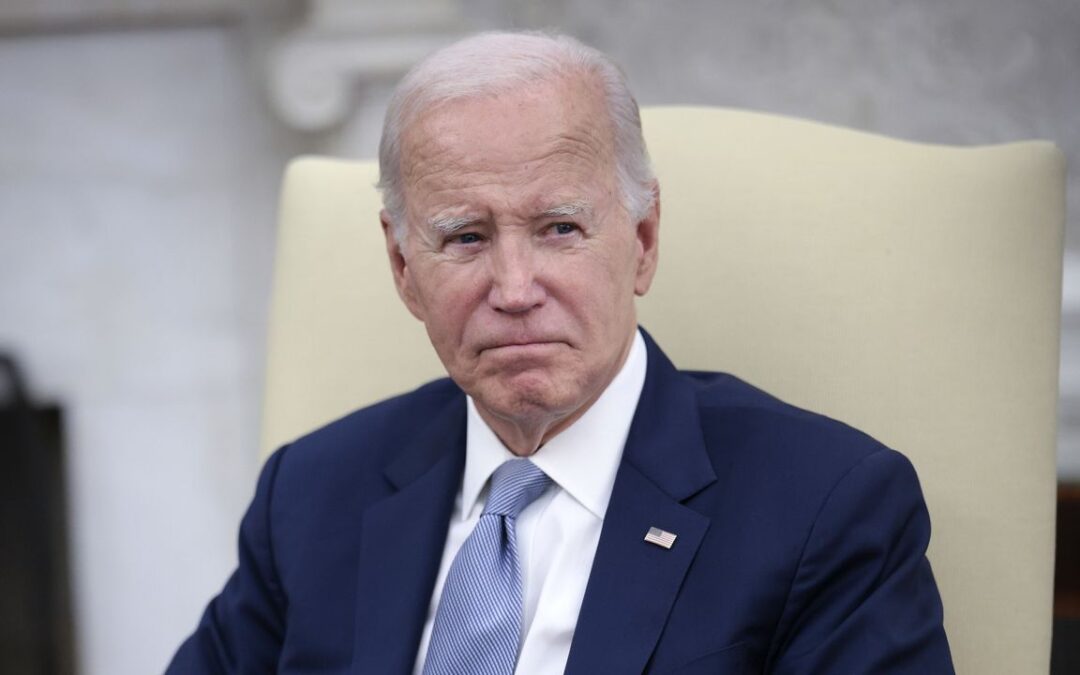

The critical task now for President Joe Biden — as he mulls retaliation over the deaths of three Americans in an attack by suspected Iranian proxy forces in Jordan Sunday – is to prevent that region-wide war from tipping out of control.

It is indisputable that the United States is again embroiled in a war in the wider Middle East, less than three years after Biden officially decreed the end of a two-decade-long combat mission in Iraq that exhausted the US and caused deep political trauma.

It is also clear that the Biden administration’s effort to prevent an escalation is not working. US strikes against Iranian-backed militia throughout the region, which followed more than 160 attacks on American military facilities, did not deter Sunday’s drone strike. And missile and drone attacks against commercial shipping in the Red Sea haven’t stopped despite rolling US airstrikes against their launch sites and infrastructure in Yemen.

So Biden has now arrived at the unenviable position that presidents often face when all potential options before them are bad and the very task of seeking to slow a deepening crisis may end up exacerbating it.

The catalogue of violence that has erupted outside Gaza – where tens of thousands of Palestinians have been killed after 1,200 Israelis died in Hamas terror attacks on October 7 – underscores the grave potential of the war.

— Hezbollah, a pro-Iranian group based in Lebanon, has been waging a low-grade war against Israel. On Monday alone, it said it had launched 13 attacks on targets in northern Israel. The Israel Defense Forces said that evening it carried out airstrikes on Hezbollah targets in Lebanon.

— Two months of Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping have disrupted global supply chains and raised the cost of the cargo trade, risking a major economic impact. The US is leading a coalition of nations to protect trade.

— The US and Britain launched strikes against Houthi targets in Yemen this month and Washington has carried out multiple follow-ups. But even Biden has admitted that the strategy has not stopped Houthi attacks.

— The US also launched strikes against targets linked to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in Syria.

— The Biden administration has also carried out attacks on Iran-backed groups in Iraq, severely straining relations with the Baghdad government and raising concerns that US troops in the country to fight terrorism could be asked to leave.

— Israel expanded its own war by carrying out a drone strike that killed a senior Hamas leader in Beirut, according to US officials, fueling tensions in Lebanon – a nation beset by severe economic, political and security crises.

— Iran has blamed Israel for an attack that killed a number of Revolutionary Guard officers in Damascus, Syria.

If there is an upside to this spiraling military activity it’s that, as serious as it is, it’s unfolding as a set of controlled escalations that has yet to acquire its own destructive momentum. Some worst-case scenarios haven’t occurred — for example, a massive onslaught of missile attacks by Hezbollah against Israeli cities. The group has a far greater capacity to hurt Israel than Hamas does.

And while the weekend attack that killed the three Americans is tragic for their families and their nation, there has not so far been a large-scale attack on US interests — for instance, catastrophic damage to a US naval ship with huge loss of life — that could multiply the intensity of the conflict on multiple fronts. The calibrated escalations have fueled an impression in Washington that Iran doesn’t want a full-scale regional conflagration any more than its arch-enemy the United States does.

But if the progression of the conflict has been steady, rather than sudden, it’s not a given that it will stay that way.

“I think it’s very important to note that this is an incredibly volatile time in the Middle East,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said Monday, before adding: “I would argue that we have not seen a situation as dangerous as the one we’re facing now across the region since at least 1973, and arguably even before that.”

Aaron David Miller, who spent years as a Middle East peace negotiator for presidents of both parties, is even less hopeful. He told CNN’s Jim Acosta on Sunday: “It’s going to get worse before it gets worse, I suspect.”